Recently I’ve started mentoring a local high school student a bit on implementing a video game, and this is a technical note toward that.

How objects move in simple arcade and action games is usually fairly straightforward, nothing more at the core than basic trigonometry and physics.

Game Loop

Most action games are a kind of real-time simulation, the core of which is a loop that updates essentially the entire world, all the objects and environmental effects in it, each cycle. That cycle is usually driven directly or indirectly by the frame rate, how many times a second the video display can or should be updated. Modern action games generally target 30 or 60 frames per second (FPS).

The relationship between frames and updates can get complex, but here we’ll assume we simply want to draw frames as frequently as possible and will update the world each time. A key detail even in this simple setup though is that a variable amount of time may pass between each update: The program will execute at different speeds on different computers, may slowdown if many other programs are open, and so on. We therefore need to account for that time in the update, so that the game plays basically the same in different environments.

The core of a typical action game program is then a loop that looks something like:

While playing

Calculate elapsed time since last update

Update each object in the world by the elapsed time

Render the current world

Calculating the elapsed time is a simple task of polling the computer’s clock. At the start of the program, the variable is set to the current time. Each update cycle, that variable is subtracted from the current time to give the elapsed time. The variable is then set to the time for this update cycle.

Rendering the world can use a wide variety of techniques, e.g., looping over all the game objects and applying a polygon drawing technique as discussed last time.

This rest of this post addresses moving objects in the world update.

Straight Line Movement

Moving in a straight line is a simple matter of displacing an object, shifting its x and y position.

In practice, game updates may happen at slightly different intervals each frame, so it’s not quite as simple as merely adding a fixed value each cycle. Instead, the object is given a velocity which is multiplied by the time interval since the last frame to calculate the object’s displacement over that period.

x' = x + xvel*time y' = y + yvel*time

Here x and y are the current position of the object, xvel and yvel the two axis-components of its velocity, and x',y'is the updated position of the object.

To set the object moving in a given direction, we simply set xvel as the cosine of that angle times the speed we desire, and yvel as the sine times the speed.

xvel = cos(angle) * speed yvel = sin(angle) * speed

As discussed previously, keep in mind that most computer trigonometry functions operate on radians rather than degrees, and because the y-axis points downward, counter to typical conventions in mathematics, 90 degrees actually points down-screen.

Inertia

For objects that don’t change direction, the above is all that’s needed. Others, like the player’s ship in Asteroids, need to change velocity, e.g., in response to player input. In most games the player doesn’t change direction immediately but instead has some inertia, slowly moving from one direction to the next rather than just jumping to a new direction immediately. This is yet another reason to base movement around velocities and simple physics rather than fixed displacements or other schemes. Many games will additionally model acceleration to easily incorporate concepts like the drag of moving on a surface eventually slowing an object to a halt, or gravity speeding an object down to the ground when it falls.

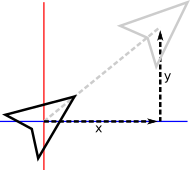

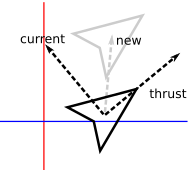

The precise implementation and numbers used are some of the key elements defining how a game feels to play, and entire tomes have been written about these primitive physics in classic games, e.g., for Sonic or Mario. In many games inertia is fairly subtle. In Asteroids though it’s an overt, characteristic feature. The player’s ship moves as though it’s in space, gliding along endlessly with no friction to stop it, simply rotating in place until thrust is applied to change course. A simple way to do this is to track which direction the ship is currently facing, and manipulate that whenever the player hits the keys to turn. The keys to thrust forward and backward then simply trigger computing a velocity for the current direction, which is added to the current velocity.

xvel' = xvel + cos(angle) * thrust yvel' = yvel + sin(angle) * thrust

Where thrust is the acceleration to apply. This is effectively taking the current vector of the ship, the new vector the player wants to move in, and adding them together to produce an updated vector reflecting the thrust applied to the ship’s inertia.

Regulate Velocity

To keep the gameplay sane we need to cap the ship’s speed at some amount. Unfortunately we can’t just check to see if either velocity component has gone beyond a bound, because then the ship’s movement will be fixed in just that axis and it will move very oddly. Instead, we need to check if its speed—the magnitude of the velocity vector—is too high, and adjust its velocity accordingly. We do the latter by normalizing it, identifying the fraction of its speed contributed by the velocity’s x and y components, and multiplying that by the maximum speed we want to produce new, reduced x and y components that together fall within the bounds.

len = xvel^2 + yvel^2 // Compute length of the vector squared; if len > max^2 then // If we're moving too fast; len = sqrt(len) // Compute the length; xvel' = (xvel / len) * max // Normalize the components and multiply yvel' = (yvel / len) * max // by our target max speed. end

Note that we compare against the square of the maximum speed because computing a square root, to get the actual length, is traditionally a time-consuming calculation, though for this example it doesn’t matter. We therefore only want to compute it if necessary, and compare instead against the square of the bound we want to impose, a computationally cheap calculation to make.

Screen Wrap-Around

Finally, a critical part of basic movement is how objects interact with the boundaries of the world, which are often simply the screen itself. That in and of itself is a major question: Is the game world bigger than a single screen? Related questions further define critical basic behavior: Does the object stop at a world edge? Bounce? Wrap around to the other side? Does it have different reactions at different edges? As one small example of the latter, my little arcade game Gold Leader gives the player more tactical options, makes the screen feel bigger, and gives gameplay an interesting twist by wrapping the player around the x-axis but bounding them along the y-axis, whereas most similar games stop them at the edge of both.

In Asteroids, objects wrap around both edges of the single-screen world. This is handled through a simple series of checks and shifts in position.

if x < 0 then x += screenwidth else if x > screenwidth x -= screenwidth if y < 0 then y += screenheight else if y > screenheight y -= screenheight

Note the additions and substractions. It can be jarring to just set the ship to the opposite side once it crosses over an edge. Hardly ever will the ship land exactly on an edge within a frame, instead it will typically have moved several pixels beyond. Adding and subtracting the dimensions preserves that slight difference and helps ensure the movement is visibly smooth.

Implementation

All of the above has been implemented in this little demo. Click on the game below to give it focus or follow that link, and then drive the ship with the arrow keys.

You can view the source to see the elements above implemented.