Sometime recently a new trailer went up for the Space Hulk: Deathwing video game. It’s pretty good:

Some of the guys have been discussing whether or not the unexpected musical selection, Kadebostany’s Walking With A Ghost, works. Juxtaposing action games with slower or offbeat music has definitely been a thing since at least the very successful, memorable, and beautiful “Mad World” trailer for Gears of War:

Given that Space Hulk: Deathwing is a Games Workshop licensee, it’s tempting to quickly dismiss the latest trailer as simple mimicry given GW’s general ineptness and the low quality of many of the offerings from both it and its licensees. However, I think the game studio developers quite possibly put a lot of thought into that selection, and that it comes close to inspired.

Synchronization

First, note how the whole video is well keyed to the music. That’s not coincidental, and took more than just slapping the song over the video. As a counter-example, note how easy it would have been to just throw Mad World over the Gears trailer. Although I don’t actually believe little effort went into tailoring that video to that music, it could have. That song doesn’t have a ton of really distinctive audio shifts, peaks, or valleys, and the action on the video is pretty subdued. They would basically work together no matter what, with no effort to sync them up. It takes a fair bit of close watching to actually pick up a few subtle touch points:

- When the lyrics go “Worn out places, worn out faces” as the clip pans from the rubble to the face of first the demolished angel statue and then has its first closeup of the face of the soldier (starting at ~9s);

- The lyrics go “No tomorrow, no tomorrow” as the soldier runs into the dying light, the video fades out, and then comes back in on yet more endless rubble and running (starting at ~22s).

- Of course the closing, with the “Mad world” chorus as the hero leaps from a minor potential confrontation with a vaguely humanoid enemy into a hopeless situation in a demonically lit setting against truly otherworldly aliens (~40s).

In contrast, Walking With A Ghost has a couple pace changes and definite valleys, all of which the Space Hulk trailer video is keyed to. Several are pretty overt:

- ~40 seconds in when the music picks up and the video goes from a setting pan and ultra slow motion to live combat;

- ~70 seconds in, the music slows down again as the video slows to show the Tyranids bringing in reinforcements;

- ~75 seconds in, the music picks back up into a more flowing style with horns giving a feeling of a Spanish bullfight or Mexican swashbuckling scene while the action picks back up, having switched to swirling swords and close combat until seguing to end with a last stand on steps vaguely reminiscent of a cathedral.

All in all, the video seems to have been certainly choreographed to the music and at a minimum the latter not just cynically slapped on in a cheap ploy to stand out or evoke some gravitas and intellectual veneer.

Lyrics

A few connections though are more subtle and tied to the lyrics, e.g.:

- ~55 seconds in, “Round and round and round” as flames and the camera swirl around a Terminator;

- ~64 seconds in, “I’m not creatin’ my flow with my ego” as the camera pans over a pretty solid symbol of ego, a powersword inscribed with “I am wrath. I am steel. I am the mercy of angels.”

With that, it’s worth looking at the full lyrics of the song:

I’m just walking with a ghost

And he’s walking by my side

My soul is dancing on my cheek

I don’t know where the exit isEvery day is still the same

And I don’t know what to do

I’m carrying my tears in a plastic bag

And it’s the only thing I got from youI have short hair

And I’m faced with a few complications

So, so if you care

Try to analyse the situation

You know, man

As the leaves fall on the ground

My soul is goin’

Round and round and roundSo please, do it well

Just break the spell

Why don’t you do it right?

I don’t want another fight

I’m not creatin’

My flow with my ego

I’m taking off my hood

And I’m entering deeply in the wood

You know, manBugs are my only food

And it puts me in a strange mood

I ain’t giving you my heart

On a silver plate

Why couldn’t we be just mates?

Oh no, never come back to me

Oh no, never come back to meI wish i could be a child, write me another dance, another chance, another romance

we could just be friendsI wish i could be a child, write me another dance, another chance, another romance

it could be the end

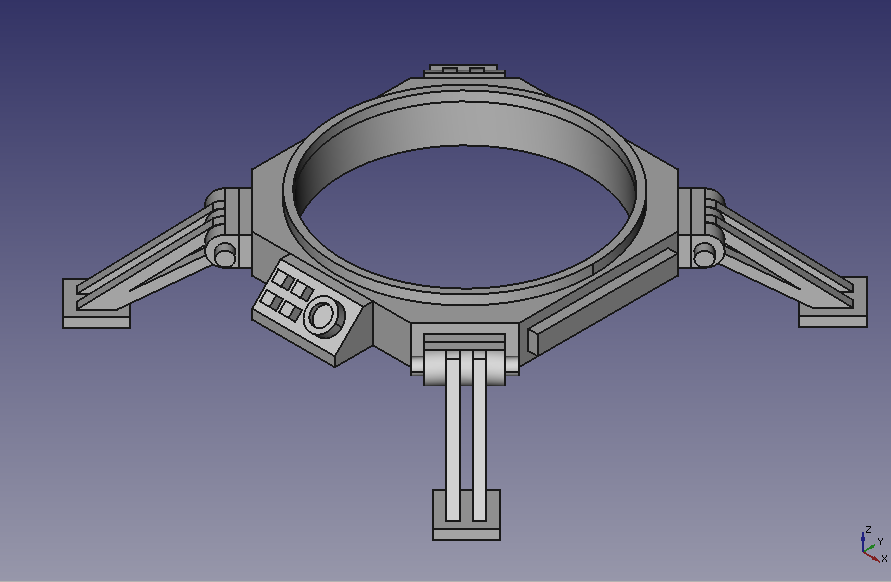

Accepting a fair dose of lyricism, that actually captures and references an awful lot about a Space Marine’s life, especially those fighting in a space hulk.

It starts with the opening lines:

I’m just walking with a ghost

And he’s walking by my side

What does a Space Marine do but trudge along with the Emperor’s will aiding his every move and his spirit foremost in the Marine’s mind?

Bouncing around a bit, there’s a middle stanza about the Marines’ monastic lifestyle and how their dedication to the Emperor and setting aside of themselves is what gives them their strength as they wade into combat against tremendous odds in dark, unknown enemy territory:

I’m not creatin’

My flow with my ego

I’m taking off my hood

And I’m entering deeply in the wood

Toward the end, it turns out we’re specifically hearing from a Space Marine fighting, probably until he dies, with Tyranids—the bugs of this particular franchise:

Bugs are my only food

And it puts me in a strange mood

I ain’t giving you my heart

On a silver plate

Why couldn’t we be just mates?

Oh no, never come back to me

Oh no, never come back to me

Most dramatically though, most of the song captures what I take as an overarching theme of the Space Marines:

I don’t know where the exit is

Every day is still the same

And I don’t know what to do…

My soul is goin’

Round and round and roundSo please, do it well

Just break the spell

Why don’t you do it right?

I don’t want another fight…

I wish i could be a child, write me another dance, another chance, another romance

we could just be friends

These lines are all about one of the central pathos of the Space Marines. They’re in many ways the pinnacle of humanity. It’s not generally readily apparent from the actual games, but these guys are all ostensibly artists and scholars without par. They’re brilliant, talented, dedicated, create great works while traveling between battles, and have built and maintain the greatest, most human, most advanced worlds and societies remaining in the Imperium of Man. But by and large, they spend all their time locked in a deathgrip with the universe, dying easily and frequently in endless combat in order to defend humanity, often times from itself.

That’s a key part of the appeal of the faction to me: Those Marines that haven’t become completely inured and numbed to that role must realize the deep tragedy of their lives. The brightest and most foresighted must futilely long for a way out of all the fighting, an impossible cessation of endless, all-consuming war. Though their personal specifics are lost to them through their conditioning (presumably—the fluff’s a bit contradictory), some of them must yearn to go back before they were inducted, when they were still children leading simple lives, unconcerned about the fate of humanity and not facing constant pain and death.

So, I would argue that even besides the choreography, the lyrics of the song actually make it an appropriate choice as well.

Conclusion

I figure there’s half a chance the producers of the trailer really did just throw on a cool song they heard that would maybe help their trailer stand out. That said, there’s little denying the whole video has been crafted around that selection. The choreography is too tightly synced, to music that decidedly requires it. At a minimum they weren’t just crassly thrown together with no effort.

At a maximum, the piece was actually chosen with some thought as to the lyrics and what’s going on in this fictional universe. Obviously all of the textual reading above is bullshit and nonsense. But it’s at least as valid as any literary interpretation out there, and I could believe it occurred to a developer if they happened to be actual fans and devotees of the 40k universe.