Someone asked on DakkaDakka today “What makes a good narrative tournament?” My club is very much committed to narrative play in Warhammer 40,000 (40k) and other tabletop wargaming, and has held a number of story-heavy events over the years. Among those, for the past seven months I’ve been organizing the monthly 40k events at my local shop (with which I’m not otherwise formally affiliated) as narrative tournaments. I’ve also played in a few other such events outside our group, notably the NOVA Narrative. Suffice to say, I’m way excited about this topic and have a few thoughts. My experience and comments are mostly ground in 40k, but all of this is generic and applicable to other games.

I note up front that I reference the NOVA Narrative repeatedly below because it’s among the most prominent and widely known narrative tournament events in 40k, and therefore among the most prominent in tabletop wargames, as well as one outside my club with which I have direct experience. A few of the comments are criticisms, but they’re meant with all due respect and as hopefully constructive notes. That’s a super fun event, it’s well executed, the organizers are amazing, and I’m devastated that I cannot by any means make it this year with the rest of my crew (I’m expecting my firstborn the week before). I do though think that some aspects of its design includes pitfalls that I would guess are fairly common for narrative tournaments, including my own events.

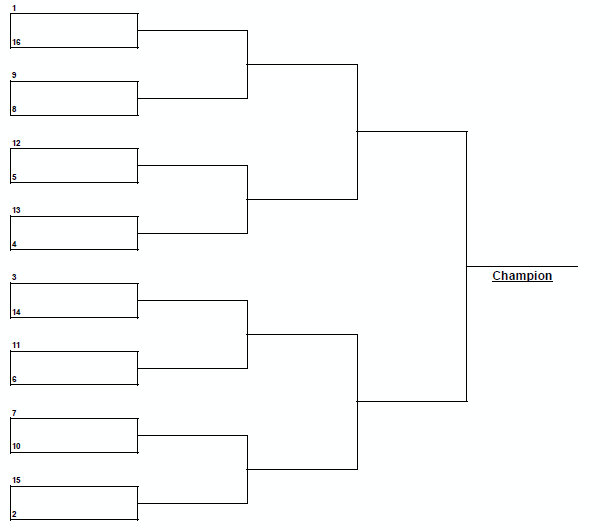

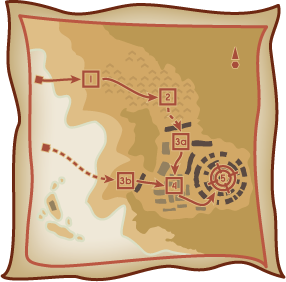

Title page from our Caldor IV campaign tournament series packet.

Narrative Tournaments? WTF?

An important opening point is establishing just what we’re talking about here. There’s definitely a valid viewpoint that “narrative tournament” is a contradiction in terms. This is aptly expressed by the first comment to the Dakka thread as to what makes a good narrative tournament: “Not being a tournament.”

Much as in wargaming overall, there’s a spectrum of organized events. On the one end are competition focused events, with more or less mathematical tournament structures, more or less tight mission design, limited or sidetrack painting & hobby components, and zero concern about fluff and story. At the opposite end is totally narrative play, with the only thing distinguishing it from casual pick-up play being that there’s a story being built or utilized, and some kind of minimal organization of players and matches. Obviously there’s a space for both. Though I’m not myself engaged at any kind of serious competitive level in 40k or any other game, I’d argue strongly that a vibrant competitive tournament scene is a good and critical thing for most games’ long term longevity and, if properly utilized by the designers/manufacturers (*cough*), actually adds a lot of value to the game even for those not interested in participating directly. But fluffy play is also great; our club has gotten immense value out of events we’ve organized purely to drive narrative. I’d also argue that most 40k tournaments at least actually aren’t very far on the spectrum toward pure competition, especially smaller, regularly scheduled shop or club events: Missions might have some wacky elements, tournament scoring often isn’t well published, there might be more or less arbitrary army composition restrictions or rules modifiers, painting and/or sportsmanship components might be significant, and so on.

I don’t think it’s a huge stretch then to fit some narrative elements alongside tournament aspects and fall somewhere in the middle of that spectrum, and there are good reasons to do so. With the monthly 40k events at our local shop, I’ve been specifically trying to see if we can get both the fluffy and the competition-oriented players engaged in organized play. Our tournament crowd is fairly well established and dedicated, but somewhat small. We do though have another contingent that’s much more motivated by narrative and team-based play. It would be great if we could run at least some events that were appealing to both and get everybody out at once. Emphasizing narrative and hobby components also tends to push against poor behavior and win-at-all-costs play.

The two event types can also bring a lot to each other. I’ll touch on this more later, but one aspect of tournaments frequently overlooked by less competition-minded players is that a typical, proper tournament pairing mechanism works toward players competing against opponents of similar skill level. That’s a great feature to incorporate into an event and try to ensure people are having fun games. In contrast, many campaign structures can unfortunately lead to devastating matchups, often repeatedly. For example, it can be tough as a new player competing in a classical map-based campaign if a neighboring opponent on your borders is a hardened, competitive veteran.

So, over the years and especially recently, I’ve been experimenting with different approaches, from riding light narrative overtop standard tournaments, to embedding tournaments and prizes inside campaigns and narrative.

We all just want to roll dice. But sometimes there’s dramatic narrative!

Storylines

“Narrative” is, of course, an imprecise term, with several dimensions: Detailed or abstract, storyline or vignette, and so on. Many of my battle reports feature a paragraph here or there with a short, isolated vignette about a particular event or character in the game, and I personally frequently consciously field lists and play with a style emphasizing dramatic, story-oriented actions in line with and developing my army’s character. Over time all those separate, simple bits of story have yielded an elaborate emergent narrative. Everybody in my club is at least vaguely aware of different major storylines of my chapter of Space Marines and its major characters. In a more top-down and a priori fashion, right now a group of 40k players in my community are running a campaign league (that I’m not in) featuring elaborate creative fiction about the armies, their commanders, and the battleground, with everything being written over time into a long-running, detailed narrative. The NOVA Narrative storyline is fairly extensive and lengthy, has emerged from the overall outcomes over the years, and for both better and worse is essentially entirely unrelated to the official 40k universe.

As a narrative tournament organizer and designer, I mostly try to keep the story fairly light, providing some theme and background while letting the outcomes themselves drive the story. The explicit narrative is usually just a few paragraphs of background text, and a short, marginally dramatized accounting in my campaign reports relating the progression of events. A good example is the report from our most recent event.

In general, I don’t spend a ton of time crafting and writing explicit narrative. Most of it’s coming from the players and exists in their head and the community gestalt, and is all the more powerful for it. My goal is just to provide basic structures enabling that better than straight tournament or pick-up play. For example, in our current campaign there’s a touch of backstory about the planet and what’s going on, but it’s very short and light. There is though a map, and on it is a Starport, which one player decided he particularly cares about, even though it doesn’t help him in-game at all and offers only modest benefits to his alliance. At some point he just came out with a short narrative that his army really wants to ensure they can get off this Emperor-forsaken rock once this war’s over and is terrified they’re going to get stuck there, so they’re fighting like hell to take and hold the Starport. He’s made that a vocal priority in the strategic discussions within his alliance, and the other players know he’s fighting for it and talk about it. That’s a great emergent narrative. At the same time, he’s also one of our better players and has been able to pursue that personal story and motivation while competing for the tournament prizes.

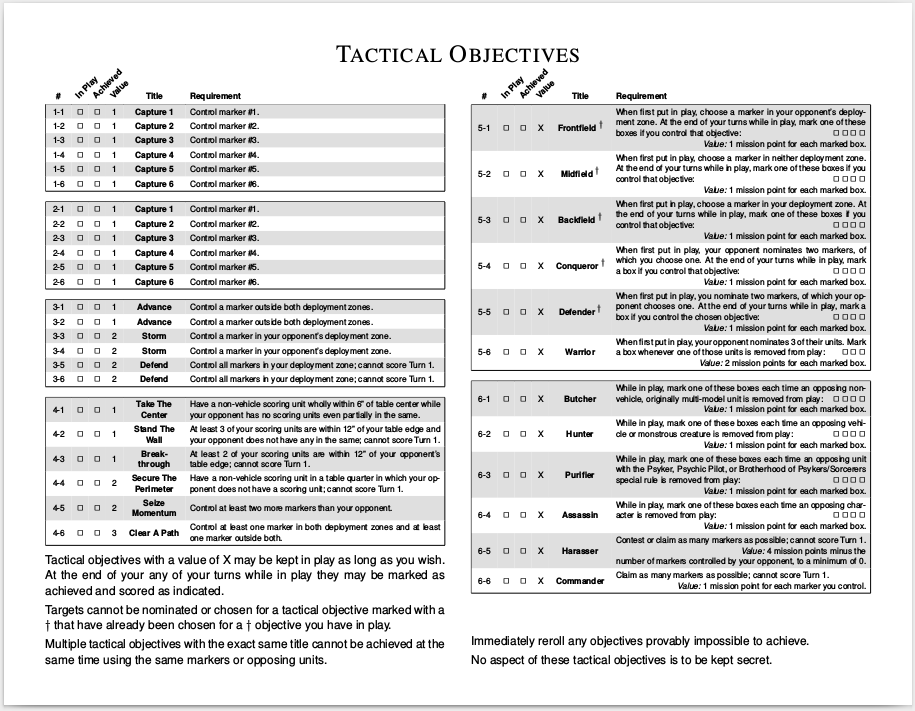

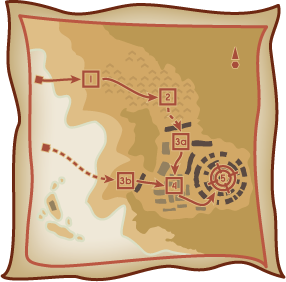

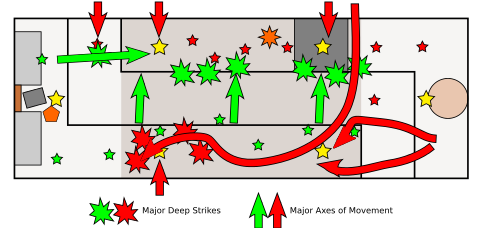

The map for our Solypsus 9 campaign, featuring the major installations.

Tournament Structures

The structures enabling that and what “narrative tournament” actually entails in practice then fall on that same spectrum above of being more or less oriented toward fluff or competition. The key things are that there’s a narrative—a story being built and/or motivating gameplay—alongside a tournament. In this context the latter is a flexible term and not necessarily a mathematical tournament structure, though it might be. I take the minimal requirement as being that there are points being awarded to individuals, standings, and prizes of some sort.

For a competition-oriented example, years ago I ran a Combat Patrol tournament league for 40k skirmishing. One of the gimmicks was that the small games (750 points) permitted the missions to be asymmetric, with matches actually consisting of two games with opponents alternating roles. Those matches though went into a pure tournament structure. Players earned individual points, pairings were straight Swiss across everybody, and there was a final single ranking of all players and prizes awarded based on that. But those asymmetric game results fed into an abstract narrative about a planet being invaded, and the Attackers and Defenders respectively fighting to advance on or defend a critical site. It wasn’t detailed at all, but it was a real story and collective narrative progression that people who cared could follow and talk about, while others could just play the tournament.

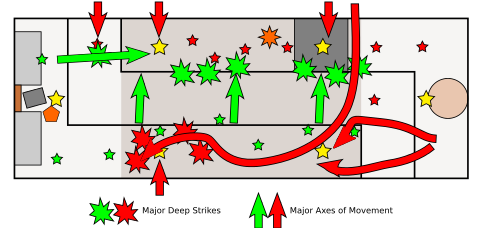

Campaign map from the 2010 Combat Patrol Tournament League.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Saturday we’re running a 40k Apocalypse mega-battle to conclude our Solypsus 9 sequence, an all-in battle royale of all the players in a single all-day game. Although my club’s Apocalypse battles are much more structured and organized than nearly any I’m aware of, that’s basically necessarily a heavily narrative-oriented event rather than a competitive one. We are though collecting entry fees and awarding store credit prizes. In part that’s to give something to the shop for hosting us, but it’ll also add some excitement and motivation. Clearly though there’s no recognizable standard tournament structure since it’s just one big match with everybody playing as teams. Instead, the match component of our scoring (we also include painting and sportsmanship) and the eventual player rankings will be based on personal in-game achievements designed to emphasize narrative play. Declare an opposing warlord your sworn enemy and then personally ensure their demise? Earn some points. Hold the site of one of your fallen characters? Earn some points. So, it’s all fluffy and loose, but it does incorporate some competitive aspects alongside very much narrative play.

Alliances

In between those two extremes are the majority of the events we’ve been running the past half year. A defining feature of these has been that players are organized into alliances and make collective strategic decisions. I specifically use “alliance” to differentiate from team-based play as in doubles tournaments, which we love and also run, including inside the narrative frameworks.

Players within those alliances don’t play against each other, caveat some significant exception, and the alliances have substantial input on the tournament pairings. In our setup they alternate putting forward a player toward some narrative action and the other alliance(s) responding with an opponent and a specific board to play on. Thus the attacker declare a campaign objective, and the defenders choose the specific physical terrain for the battle. The NOVA Narrative works very similarly, and I would guess this is somewhat common and a major feature of what most people identify with “narrative tournaments.” Notably, this arrangement is derived from some of the major team tournaments, another instance of serious competitive play contributing a more generally useful structure.

On the one hand, this is a huge draw for a lot of participants. The games themselves remain standard and players field their full armies, but they also get to enjoy teamwork and cooperative strategizing. Depending on the complexity of the narrative framework, alliances might have a ton of discussion about campaign level strategy and decision making. Certainly there’s typically a lot of discussion about which armies are the best to put forward to take on any defender, or which should be held back to try and respond to specific attacking armies, and so on. Lots of people really love and are excited by those discussions, and to a large extent those that aren’t can just ride along.

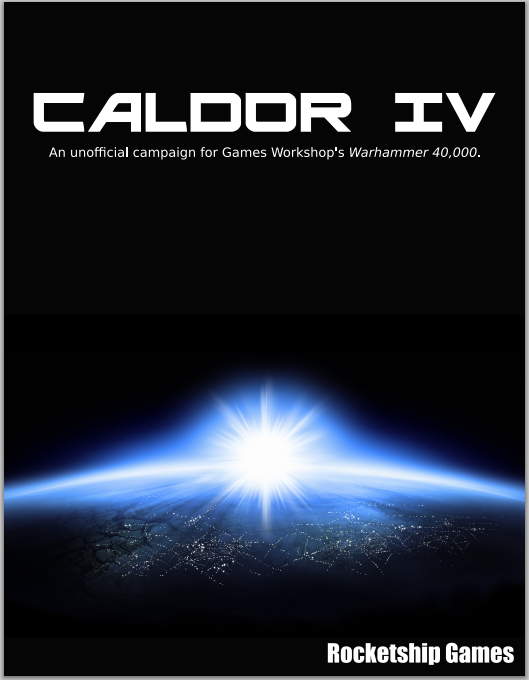

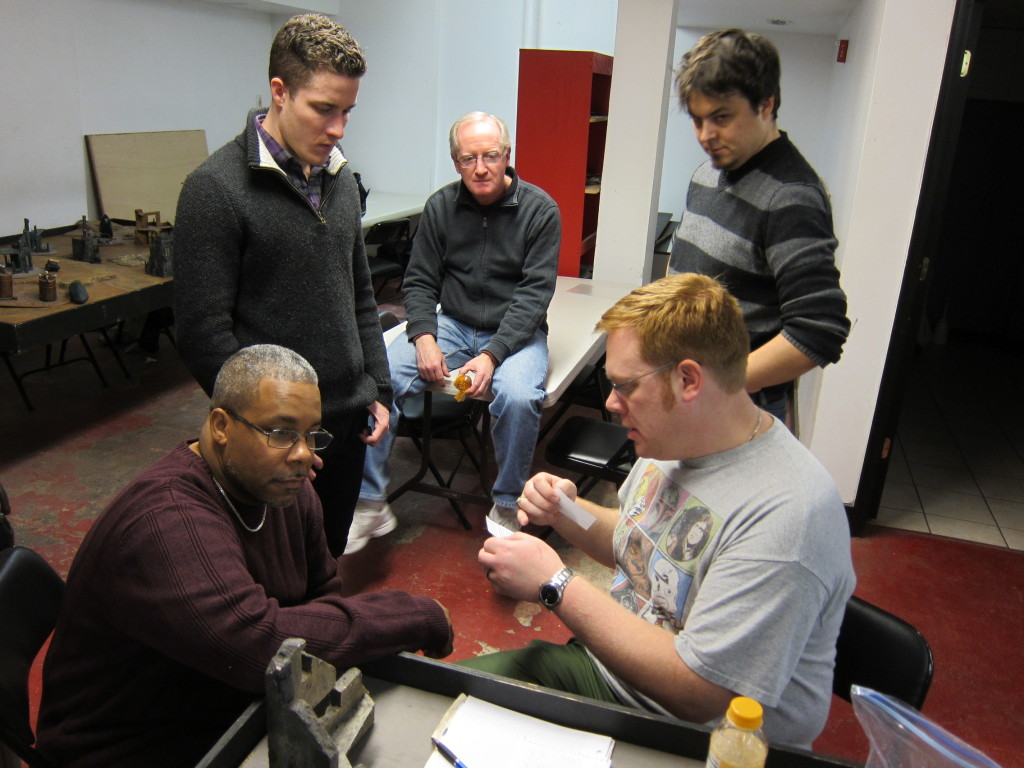

Kramer Doyle, humanity’s commander, sends the Kingbreakers off to space to do battle against unimaginable enemies and impossible odds. A Humanity Commanders’ strategy session at last year’s NOVA Narrative.

That said, this is a huge tradeoff in narrative versus competition. As soon as players are divided into alliances, it’s difficult to have a single set of final individual rankings. In particular, the top players may not face each other and will be difficult to compare. But in many settings that’s ok. Toward that, we keep our prizes small and spread them around, so that they’re spice and a fun side thing rather than serious objectives and something to be aggressively competitive about. Our prizes are generally organized as follows, depending on the number of players:

- Equal prizes go to the top player in each alliance based on match points + hobby scores + sportsmanship;

- Next prize goes to painting and craftsmanship based on player voting;

- Next prize goes to the player from any alliance with the highest match points;

- Next prize goes to a raffle of nominated dramatic moments or great plays;

- And start back over at lesser value.

That’s worked out well in our environment. Once or twice the top prizes haven’t gone to players who had the actual highest scores (i.e., the 2nd highest scoring player was on the same alliance as the 1st), but usually they actually do, and the prizes are small and spread around anyway so it’s no big deal. Similarly, although the NOVA Narrative has a variety of prizes, individual standings, and is actually a tournament, that’s all downplayed enough in favor of just playing the campaign that I actually had to consider for a moment whether or not that was the case. Besides accommodating narrative mechanics, this diffusion of prizes and the small stakes tends to work against overly aggressive and poor behavior and is an approach we had previously adopted in non-narrative tournaments.

Of more concern to me is that organizing into fluffy alliances according the allegiances and relationships inside the game’s fiction universe tends to result in roughly the same groups of players and game factions facing off against each other all the time. At some point Necrons should themselves have to fight against their own hateful Decurions, which they never will if they’re always together in the same alliance. Players in this scheme also may not get to play against particular friends if they’re in the same alliance, there might be intrinsic imbalances across the alliances based on their available forces, and so on. Our events this summer are not going to be implemented this way, so that we break up the alliances for a while and players face a larger set of opponents and factions.

Alliance tokens for the Solypsus 9 map.

The biggest concern about this style though is that it doesn’t intrinsically balance players like proper, Swiss-pairs styled and bracketed tournament pairings eventually do. It’s very easy for alliances to generate a lot of theories about who might be best to put forward based purely on factions or lists, and not at all take into account player skill and results, something I’ve seen at both NOVA and our events. That can be unfortunate if newer or weaker players wind up repeatedly set against much better opponents or armies. To some extent we’ve worked to mitigate that by having alliance commanders guiding the discussions and explicitly coached to keep fair pairings in mind, accounting for actual skill and results rather than just theoryhammer.

Recently we’ve also attempted to explicitly address this mechanically by scoping the set of players that may be put forward as a response, i.e., only opponents with similar scores/results/bracket can be matched against an attacker. That way a baby seal can’t be just thrown into a clubbing. This year’s NOVA Narrative is enacting very similar controls by breaking the pairing process up into battle groups determined by rankings within each alliance, with comparable groups coordinating matches. If an event is relatively large these mechanisms can entail significant logistical effort to work out the valid possibilities and present them to the alliances, particularly as they don’t fit within essentially any tournament scoring software, but are worth it.

In smaller groups though it can be infeasible to both apply such restrictions and have enough pairings. After all, even two alliances cuts in half the number of possible opponents. Mechanics and plausible narrative justifications for pairing players within alliances if necessary are certainly feasible, but can be tricky and work against the fluffy narrative. Ultimately these alliance-controlled, deliberate pairings are a major design tradeoff with pros and cons. They’re a major positive feature of many narrative events, but organizers should be aware of these downsides.

The Legions of Discord stare into the abyss after a rough first round in the opening event of our Caldor IV campaign tournament series.

Narrative Effects

Another big design point is how the narrative or campaign interacts with actual gameplay and tournament execution. Alliances are a big tradeoff on the latter. But many non-tournament campaigns and narratives employ asymmetric missions, award army or model buffs, and have other impacts on the games themselves.

That’s difficult to work into a narrative tournament setting because they’re quite likely to impinge on the integrity of the competition, and these features unavoidably skew the event more toward narrative versus tournament. Depending on the group and the event’s goals that might be perfectly acceptable, but generally needs to be very carefully designed and balanced. The more clearly an event is advertised toward narrative play the more that can be done in this direction. However, unless they’re very committed to a campaign or narrative, it’s ultimately hard over time for any players to accept and be excited about meaningful advantages being given to opponents in actual games, which is a detriment to the success, popularity, and longevity of any event.

Related, any gameplay effects generally need to be as simple as possible. Much tabletop wargaming and 40k in particular is already so varied and complex that many players struggle to play quickly, let alone keep up with all the opposing factions. That’s exacerbated by time constraints typical of a single-day tournament, though a league format might be more amenable. Additional boutique gameplay modifications will only slow down games, press time bounds, and potentially frustrate players.

Banner for the Solypsus 9 campaign.

As an example, the NOVA Narrative features extensive gameplay changes which probably took a lot of effort to develop and have some positive features, but for some players can also detract from the overall experience. One part is a series of optional supplemental rules and army composition tweaks for each game faction. In some cases they do actually make weaker factions more competitive, but in others they arguably buff already very strong armies. Worse, these new rules add to the whirlwind of faction rules and exceptions in 40k. Our club already had a confusing discussion about army list construction for this year’s NOVA when it became difficult to track what rules were in the official books, and what were from the event’s narrative supplements. NOVA Narrative also has extensive terrain rules and other board effects contingent on choices made by the alliances and what theater the battle is representing. A positive aspect of these are that they add a lot of alliance strategy, e.g., determining which army is most likely to survive the meteors falling on some boards. On the other hand, these are a whole new set of mechanics to be remembered and then applied in-game, in some cases with fairly substantial random effect.

From my own events, recently I tried to add essentially warp rifts and ghosts to a few missions in order to tie in some of the overall story elements into the gameplay. Some people were interested, some were not, one was terrified because the leadership effects were going to be a huge problem for his Ork army. In the end though nearly everyone forgot to apply them consistently or at all, and my effort toward these was wasted and that narrative-to-gameplay tie-in failed.

Even the core 40k rules demonstrate this, in the Mysterious Objectives rules that apply different random effects when units first claim ground objectives. In my experience, many if not the majority of players consciously or unconsciously forget about these entirely even when tournament organizers include them in missions, because they can be unbalancing, though generally minimally, but are always unpredictable and yet another, in this case non-critical, mechanic to be remembered and processed.

In contrast, everyone loved and remembered to apply a recent mission scenario of ours featuring two large guns placed at board center which they could fight to control and turn on their opponent’s army using more or less standard shooting mechanics from the fundamental core of the game. Those gun emplacements combined five critical conditions for successful narrative game effects:

- Simplicity: The mechanics were simple and straight from the standard game, fast and intuitive for everybody to execute;

- Predictability: Players knew what the guns would do well enough to strategize around them;

- Control: The players themselves took concrete actions to enact and target the guns, rather than just rolling out random effects automatically;

- Balance: Both players had an equal opportunity to utilize the effects, and they had about equal potential impact on a variety of different army types;

- Advantage: Big guns offered a clear incentive for the players to both remember to utilize them, and to take efforts to do so—nobody forgot about those guys.

Because of the issues above I’ve by and large been restricting narrative effects to the campaign or story itself, isolated from actual gameplay. That way if they’re imbalanced people are still winning and losing their personal games fairly, games are kept straightforward, and people not interested in those aspects don’t have to deal with it.

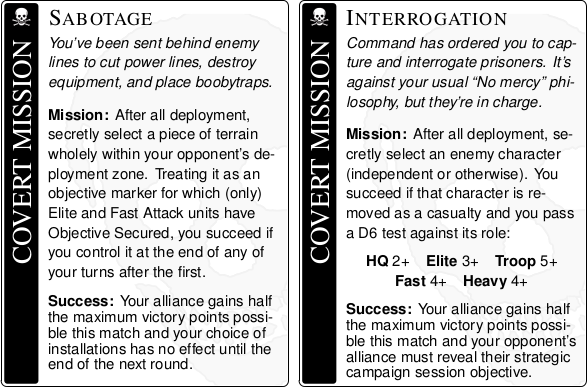

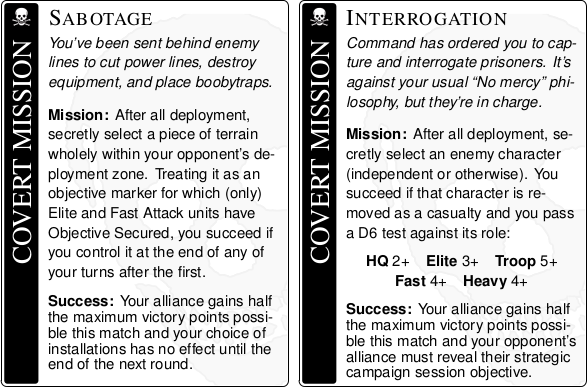

But limited mechanics that meet those five characteristics can tie narrative and campaign structures into actual gameplay even within a tournament. A very successful example of this from the NOVA Narrative that we’ve adopted into our events are Covert Missions. These are simple additional objectives given in secret to the players of the trailing alliance. Their primary effect is to help keep the sides roughly even and maintain the campaign tension. But they also give players with little hope of winning their match something else to achieve even in the face of defeat. The rewards though only apply to the narrative or campaign and the alliances’ standing, so they don’t unbalance either particular matches or individual rankings. As such, they meet all of the criteria: Written correctly they’re simple and straightforward to apply; they’re a known effect the player can actively play toward; they don’t in any way imbalance the games or tournament; and they offer a real, tangible award to the player. All told, they offer a strong narrative aspect while also being totally ignorable. In practice though, hardly anyone will set them aside. Many players I’ve seen at both NOVA and our events have felt more than redeemed to get crushed in a match but secure the covert objective for their alliance, while other competitive players have been disappointed to win a match mighitly but not achieve their covert mission.

Two sample covert missions from our Solypsus 9 campaign.

Expectations and Comp

The last major aspect to touch on is setting expectations and controlling the tournament environment. Again, “narrative” means a lot of things to a lot of people. It could mean bringing a fluffy army scrupulously designed to match creative personal fiction or canonical game universe details even at the cost of effectiveness. Or it could mean throwing all your biggest, most expensive and rare and powerful models on the table because they’re the most dramatic units in your faction’s background and damn that’s good narrative! In many cases those two approaches don’t exactly line up well, to say the least, and the clash of expectations can easily frustrate players.

This is the only real negative I and others in my club have with the NOVA Narrative, that it doesn’t control for this mismatch (unless we’ve missed some update for this year’s event). For example, it looks like the very much competition-oriented Grand Tournament track of the convention will actually impose greater restrictions and debuffs to (arguably) overpowered units currently in 40k than the Narrative will. That’s asking for trouble if one player understands the latter event as a relaxed, casual, story oriented event, and another reads it as anything goes because it’s “not a real tournament” or simply has a different idea of what’s overpowered or not.

In our events we have been fortunate that there’s a fairly solid community consensus on what’s appropriate, most people are prioritizing mutual fun, and we have some favorable basic demographics—the older and better resourced players are largely narrative oriented and relaxed, while the more competitive players are mostly too young and too restricted financially to readily whip out the latest face stomping units.

Yep. Trouble ahead.

We have though worked to systematically address these kinds of potential problems in a few ways, for both our narrative and more traditional competitive events, and through the few relatively minor troubles encountered have seen them to have effect in encouraging a more positive environment:

- Reintroducing basic hobby scores, via a straightforward and objective 5 line metric (all models assembled; all models painted; all models based; some models advanced painting; some models advanced basing).

- Reintroducing two-factor sportsmanship scores (scores per match, and then ranking enjoyable games).

- Incorporating a variety of awards and having more rather than larger prizes.

- Significantly debuffing classes of units deemed problematic by the community through mission scenarios and scoring, rather than actual gameplay rules changes or outright bans.

None of these problems or solution approaches are unique to narrative tournaments, but the issues are potentially exacerbated by trying to straddle both story-oriented and competitive play. Organizers of these events should be especially carefully that event advertisements and mechanics are properly aligning and enforcing expectations.

To the larger picture, emphasizing narrative and team oriented structures is itself in part a useful tactic to preemptively discourage hostile play and poor sportsmanship. Narrative play also offers opportunities for less skilled players or those fielding intrinsically disadvantaged factions to attain achievements, contribute to a team, or simply develop a good story and have a good time even while losing matches overall. These are major motivations for adopting these kinds of events and elements.

Campaigns

To conclude, we have online some examples and mechanics writeups from our 40k events that may be of interest or use to potential narrative tournament organizers.

Our current campaign is Solypsus 9, which featured four months of campaign tournaments fighting over a map, and concludes this weekend with an Apocalypse game. Campaign reports have all been posted including some implementation overviews, and a draft of a more formal writeup of the map mechanics is also posted. The map campaign is essentially an entire boardgame in and of itself, much like Diplomacy or Game of Thrones. It enables the alliances to make real strategic decisions in their campaign over the map, but without requiring significant player commitment. They can easily drop in and out of the campaign as they show up for different events or not, change alliances to play a different army, etc., without penalizing themselves or their alliance. The map also ties strongly into the concluding Apocalypse scenario.

The bugs make planetfall on Solypsus 9.

Previous to that was our Caldor IV campaign. The first round was a campaign tournament using some simple mechanics to develop a solid narrative tracking the alliances’ search for a specific relic and a missing VIP. Next was a 40k Kill Team styled skirmish campaign using our improved in-house Recon Squad variant. In that players work to achieve specific legacies, e.g., Sentinels were trying to defend installations, while Assassins were trying to assassinate leaders. That sequence concluded with a mini-Apocalypse team battle. Campaign reports for each were posted, and a draft polished writeup of the mechanics is also available. Some of the text is not complete, but the search mechanics are written up, along with all the cards needed for that as well as the skirmish legacies and missions. A notable aspect of the search mechanics are that each alliance has a definite, randomized story and progression, but it’s perfectly secret. Even the TO can play and not know the outcome or any special information.

As mentioned early in this post, some years back we ran a Combat Patrol tournament league that had a very slight narrative, but was an unadulterated tournament with true pairings and standings. Each mission featured asymmetric setup and goals, with matches consisting of two games with players alternating sides. The results then fed into a very simple narrative about the success or failure of a planetary invasion and quest for a specific site, wholly abstracted from specific players and even alliances. Those missions and a few details are still online.

Although not a tournament, for years our club has also had a series of annual Apocalypse matches that have developed an important shared club narrative over the years. Most of that has been developed with few mechanical connections and instead mostly through forum discussions, telling tall tales, and the shared experience. However, there have been some connections, such as specifically crafting this year’s scenario as the final siege at the end of an epic campaign. The battle report talks a little bit about bringing those narrative elements and balance into a fairly large Apocalypse battle.

Recap of this year’s Apocalypse grudge match, The Fall of Kimball Prime.

Forge the Narrative!!!

All in all, our experience has been that although not without its challenges and certainly including some tradeoffs, “narrative tournament” is by no means a contradiction in terms. Such events can actually be highly rewarding and enjoyable for a large swath of players, as well as working toward larger community goals. We’d love to talk about it more, and if you’re in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (USA) area you should come out and join us!