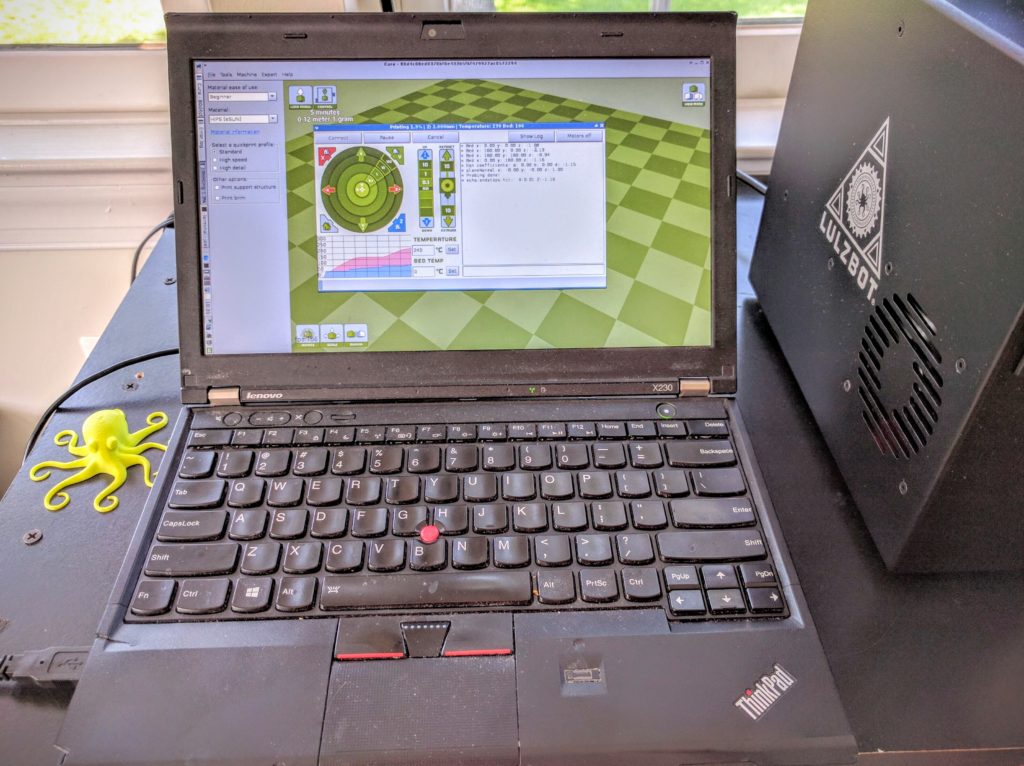

After years of thinking about it I finally got a 3D printer. Several models currently on the market at last hit the combo of price, print quality, and ease of use for which I’d been waiting. I haven’t done much with it yet, but so far it’s really exciting. Getting it set up and making my first print was wondrously easy, even in the somewhat obscure variant of Linux I use. Similarly, I was able to whip together a quick test part in a simple 3D modeler that was vastly quicker and more intuitive for that small job than the engineering CAD tools with which I’m familiar, and browser based to boot.

I have just three thoughts to share while I listen to the servos on another print.

Magic

One is just a reflection on the shocking banality of magic. This is a magical device. And yet it sits on my desk, at home. The whole process is magic:

- I order a very complex assemblage of electronics;

- Not 24 hours later it’s delivered to my door, at no shipping cost;

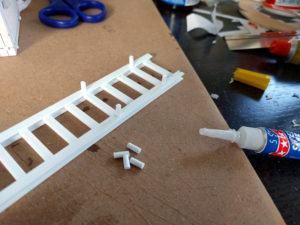

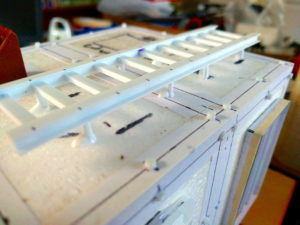

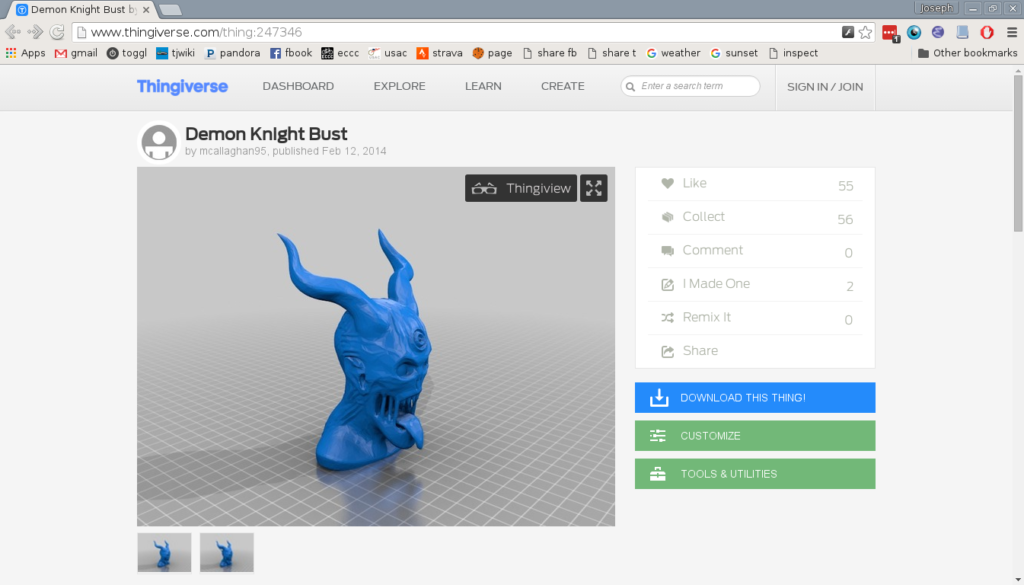

- I go back online and find some crazy mini-sculpture on a lark;

- A simple tool lets me examine the model and send it to the device;

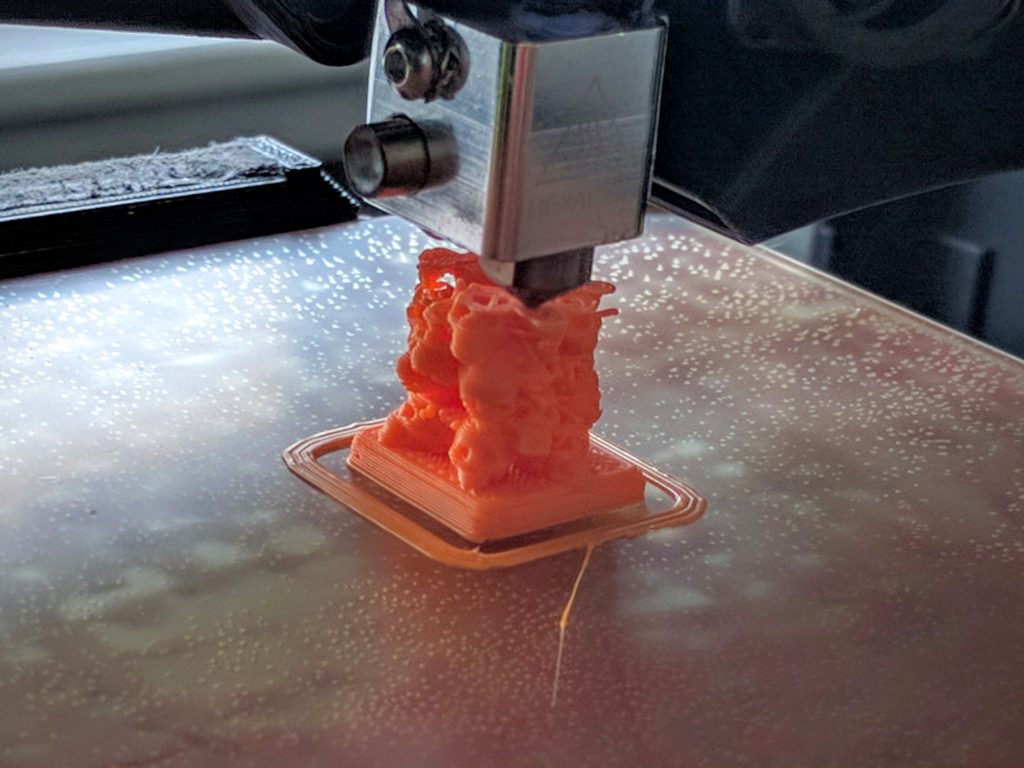

- Minutes later I have a good quality 3D replica on my desk.

Nearly everything about that sequence is almost so easy to overlook today. Having an uncommon, advanced electrical appliance delivered almost immediately is a concept that would have been all but unfathomable to regular consumers even ten years ago, and very expensive five years ago. The whole Internet component of that process is itself such deep magic taken so trivially for granted these days. But producing a complex physical artifact is still this moment just rare enough that it highlights the heights of sorcery which we have brought into our everyday lives.

Just, you know, surfin’ around, lookin’ for some demon knight sculptures to turn into physical artifacts. Typical Thursday.

I saw my first 3D printer some seventeen years ago. As a college freshman, already working in two research labs, I tagged along on a trip to a conference on solid modeling. One of the corporate vendors in the exhibit hall was demoing a 3D printer for rapid prototyping in mechanical design. Some of the features are still not that common: It had two extruder heads, so they had a great demo wherein they printed an enclosed gearbox as one solid piece using two materials, dunked the piece in solvent to dissolve one of them, and produced a functional, intricate mechanical drivetrain that would be near impossible to build out of separate components.

At the time that demo was amazing, science fiction. But today, you can readily buy that kind of dual-head capability for home use. My printer does not have two heads, but I could buy or make an upgrade to do so. And it’s likely that the resolution on mine is as good or better as on that extremely expensive machine I saw then.

Sometimes it’s surprisingly difficult to see technological progress, either because it’s invisible or actually hasn’t happened. Just to pick two examples: It’s difficult for most people to really appreciate the improvements in automotive technology that actually have been made, as the real developments are all literally under the hood and body and mostly show up in absentia, via dramatic reductions in fatalities and pollution. Meanwhile, a true lack of progress, much of America still has barely better Internet access than it had when I was growing up on dial-up.

But this device is concrete and tangible progress you can put on your desk. Over just the course of my adult life so far, less than two decades, 3D printing has advanced from a technology just starting to transition beyond a research concept, to one rapidly becoming a household commodity appliance.

An exemplar of one of the world’s most advanced technologies! … being used here to print a literal tower of skulls for next month’s boardgaming …

Science

My second thought is that, of course, this has happened before. One of my very earliest memories is the soft blue console glow from the Commodore 64 that my dad put in my bedroom as a very young kid. There has effectively never not been a computer in my life, and the profound impact that early, constant exposure and intimate familiarity has had on my career, friendships, and life is incalculable.

Demographically though I am certainly on the leading edge of the populace for which that could have been the case. Even up through to high school it was just starting, even in middle class circles among the more education-committed households, to be reasonable to assume that people had a computer at home. And yet, the middle class and up cohort born then will essentially all never have known a life without computers. Over that fifteen years or so PCs had advanced from new, somewhat obscure technology, to a near ubiquitous household item.

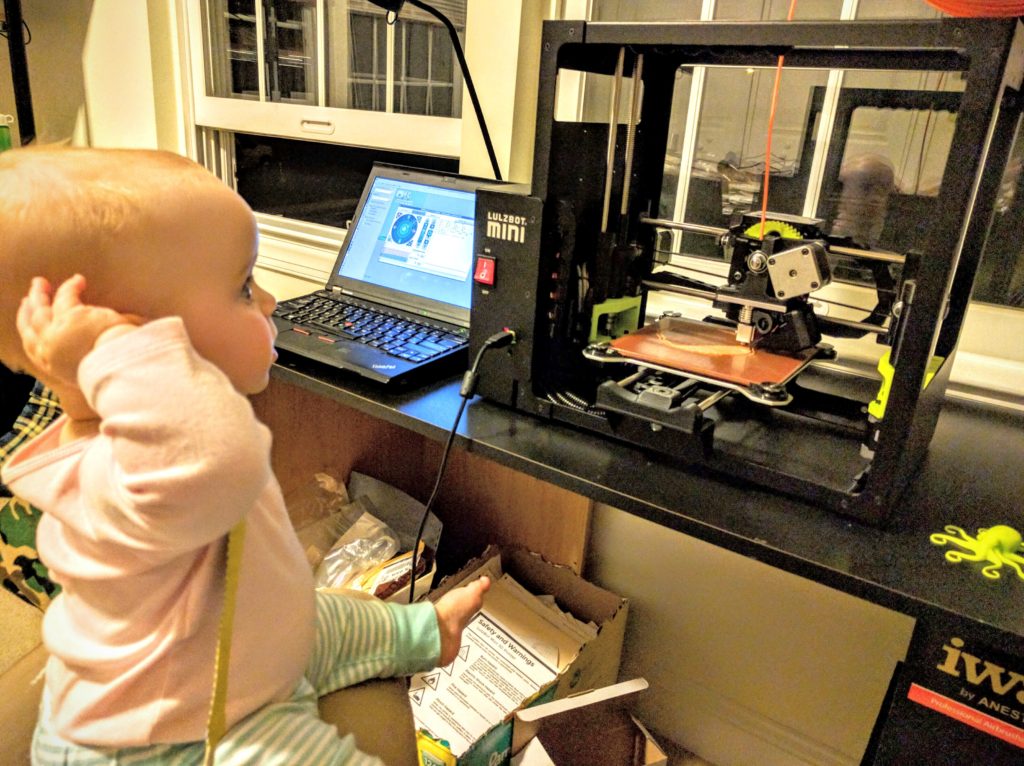

As a new father then, it behooves me to think—and worry—about what is next. My wife was teasing me earlier than our daughter is going to grow up thinking that everyone has a 3D printer. But that’s exactly right, everyone will. Not next year, not the year after, but absolutely by the time our baby is in high school and quite likely while she’s still in elementary school, these are going to be everywhere. Right now you can walk into several big box chain stores and pick up a 3D printer for a few hundred dollars or less. Granted, those models might not be that capable or that robust. But that’s only a question of time. This isn’t a technology that’s coming, it’s already here, already massively changing engineering and design, and poised to change business and everyday life. Being immersively fluent in 3D modeling and rapid bespoke manufacturing is going to have the same magnitude of bearing on being a scientist, engineer, or any number of other careers that computers had for my cohort. So, yes, our daughter will always have one of these around.

Change

The follow-up question is then: What else? 3D printing, drones and autonomous vehicles, massively capable AI, ubiquitous gene hacking, these are all coming, probably in that order. “When?” is inarguably a matter of huge uncertainly, but almost certainly well within the timeframe in which I need to worry about putting my baby ahead of those waves reshaping the world.

Fortunately I am professionally and personally disposed to be fluent and comfortable with most of those. But gene hacking? I only know the most rudimentary, textbook aspects. More troublingly, what else am I missing, what imminent paradigm change is not on my radar? Once upon a time and still ongoing, computers changed everything. An awful lot of people didn’t see that coming. But now there are upheavals looming not just in practical work and daily living, but basic conceptions of production, privacy, creativity, science, and even personhood. How to prepare a little person for an onslaught of change that will be deeper and faster than anything to come before, and will likely only get deeper and faster?

That prospect should be scary. In many regards it is terribly so. Humanity as a gestalt is tragically unprepared to harness and manage these disruptions.

On an individual level though, the true fundamentals will remain so even as the world qualitatively changes. Direct familiarity with the tools will always matter, and it’s grossly unfortunate that inequality in access seems poised to only grow with time. But humanity’s ultimate toolset will always be the same: Critical thinking, curiosity, empathy, our intelligence and values. Just as determinative as my newfangled home computer to my comparative success navigating the information age were much more time-honored assets: The shelf of encyclopedias and dictionaries we had within kid-reach, and the weekly trips with mom to the library, hauling home stacks of Encyclopedia Brown, Star Trek, and Shakespeare.

So, this afternoon, baby and I will probably play with the 3D printer just a little bit. It is, after all, a pretty cool robot. But then, just like most days, we’ll read our increasingly tattered copy of Where’s Hedgehog?, crawl around exploring under the tables, and give big hugs to Zebra-Giraffe and all our animal buddies. Because, just as they have always been, these are the root skills, traits, and values I can give her that are going to help her through even the changes to come that I cannot possibly foresee. Thinking, curiosity, empathy. In the end that’s all there is under everything, no matter what new and magical forms the world takes.